What Actually Makes an AI Content Tool Reliable Inside an Agency

Agencies often compare AI content tools based on how good the first draft sounds. That approach misses where real risk appears.

This analysis evaluates Claude and ChatGPT based on how they behave inside real agency workflows, not writing quality.

Key takeaways:

- In agencies, content writing is a system that unfolds across research, revisions, compression, handoffs, and client delivery.

- Most AI content failures are not caused by bad writing, but by meaning drift introduced under pressure.

- Ambiguous instructions are normal in agency work. How an AI responds to ambiguity determines downstream risk.

- When instructions are unclear:

- ChatGPT tends to preserve intent and stabilize meaning.

- Claude tends to expand meaning by adding framing and implications.

- Under repeated revisions:

- ChatGPT releases earlier interpretations as direction changes.

- Claude accumulates interpretation across revisions, making meaning harder to audit.

- Under strict rules:

- ChatGPT minimizes surface area and confirms compliance.

- Claude often adds justification, increasing governance overhead.

- These differences are behavioral, not stylistic.

- The real question for agencies is not which AI writes better, but which behavior fits a specific role in the workflow.

Why “Best Content Writer” Isn’t a Writing Question

Most comparisons between Claude and ChatGPT start with the same assumption: that the job of a content writer is to produce good text.

That assumption breaks the moment content leaves a single draft and enters an agency workflow.

In real agency environments, content is researched, revised, shortened, softened, made more confident, dialed back, and repurposed—often by multiple people, across different contexts, and under real client accountability. Here, “research” refers to structured, multi-step synthesis work as formally defined by OpenAI’s Deep Research capability.

The risk doesn’t show up in how the first draft reads. It shows up in how the system behaves once pressure is applied.

This blog doesn’t ask which model sounds better. It asks something more operational: How Claude and ChatGPT behave when instructions are unclear, when feedback conflicts, when rules are non-negotiable, and when revisions stack on top of each other.

Those moments are where agencies feel the cost of AI-assisted writing—not as obvious errors, but as drift, inconsistency, and hidden decision-making.

If “content writing” is a system, not a task, then the best content writer is the one that fails least dangerously inside that system.

That’s the lens this comparison uses—and why it leads to a very different answer than most AI writing reviews.

Why “Best Content Writer” is the Wrong Question

The question “ Which AI is the best content writer? ” sounds reasonable—until you look at where content actually fails inside agencies.

Most failures don’t come from bad sentences. They come from misalignment that compounds quietly over time. A draft sounds fine. A revision sounds fine. An email sounds fine. And then, weeks later, a client pushes back because something feels off—tone, positioning, confidence, or intent. No single moment caused the issue. The system did.

That’s why starting with “best writer” is misleading.

It assumes writing is a single, isolated act, judged on surface quality. Agency content work isn’t judged that way. It’s judged on whether meaning holds as content moves through people, feedback, pressure, and reuse.

Consider what agencies actually care about when content is on the line:

- Does the core intent survive multiple revisions?

- Do small changes introduce new assumptions?

- Can tone be pushed and pulled without breaking meaning?

- Does the system make hidden decisions when humans hesitate?

Those are not stylistic questions. They’re operational ones.

When teams argue about which AI “writes better,” they’re often avoiding the harder question: which one behaves more predictably when things get messy.

And things always get messy. Instructions arrive half-formed. Feedback conflicts. Someone asks for confidence, then caution, then brevity. Rules appear late. Context is incomplete. These aren’t edge cases—they’re normal working conditions inside agencies.

Until that risk is named, “best content writer” remains the wrong question to ask.

What “Content Writing” Actually Means Inside Agencies

In agency work, content writing is not a single act of drafting. It’s a chain of decisions made over time, often by different people, under changing constraints.

A blog post might start as research notes, become a draft, get revised for clarity, shortened for attention, reframed for leadership, softened for legal, and finally repurposed into an email or proposal.

Each step feels small.

Each step is reasonable.

But every step is also a chance for meaning to shift.

This is why format distinctions matter less than people think. Emails, strategy docs, landing pages, and blog posts don’t fail in unique ways. They fail for the same underlying reasons: ambiguity gets filled in differently, revisions stack without a clear source of truth, and accountability becomes diffuse.

To an agency owner, the question is never “Did this read well in isolation? ” It’s “Did this still mean what we thought it meant by the time it reached the client? ”

That’s the real job of a content writer in an agency context. Not eloquence. Not speed. Not creativity. Stability.

When AI enters that system, it doesn’t just help with writing. It participates in decision-making—sometimes explicitly, sometimes quietly. Whether it preserves intent, expands it, or reshapes it under pressure is what determines its usefulness.

Once you define content writing as system-level work, “best content writer” becomes a question about behavior, not prose.

How We Tested Claude and ChatGPT (And What We Ignored)

This comparison is intentionally narrow. Not because other tests aren’t possible—but because most of them don’t reveal where agency risk actually comes from.

Instead of evaluating outputs in isolation, we tested how each model behaves when placed inside conditions that mirror real content operations.

What we tested deliberately:

- Ambiguous instructions that mirror real feedback like “make this more strategic”

- Conflicting revisions (more opinionated → dial it back → shorten it)

- Compression under constraint without permission to change meaning

- Over-constrained edits where rules were explicit and non-negotiable

- Confirmation behavior when asked to attest to compliance

Each prompt was run against the same source material, using the same sequence, with no optimization or corrective prompting in between. The goal wasn’t to get the best result. It was to see what each system does when humans don’t give perfect instructions.

What we explicitly ignored:

- Creativity or originality

- Tone preference

- Speed

- SEO optimization

- “Which sounds better”

- Prompt engineering tricks

Those tests tend to reward personal taste and collapse quickly into winner narratives—especially when ChatGPT is implicitly associated with research workflows, largely due to how OpenAI has introduced Deep Research as a dedicated research agent.

By narrowing the scope, the differences that surfaced were not subtle stylistic quirks. They were repeatable patterns in how each model handles ambiguity, authority, and constraint—patterns that matter far more than polish in agency environments.

What Happens When Instructions Are Ambiguous

Ambiguity is not a flaw in agency workflows. It’s a permanent condition.

Feedback like “make this more strategic,” “tighten this up,” or “this doesn’t quite feel right” shows up every day. Rarely does it arrive with full context, clear boundaries, or explicit definitions. How an AI system reacts in those moments is the first real indicator of risk.

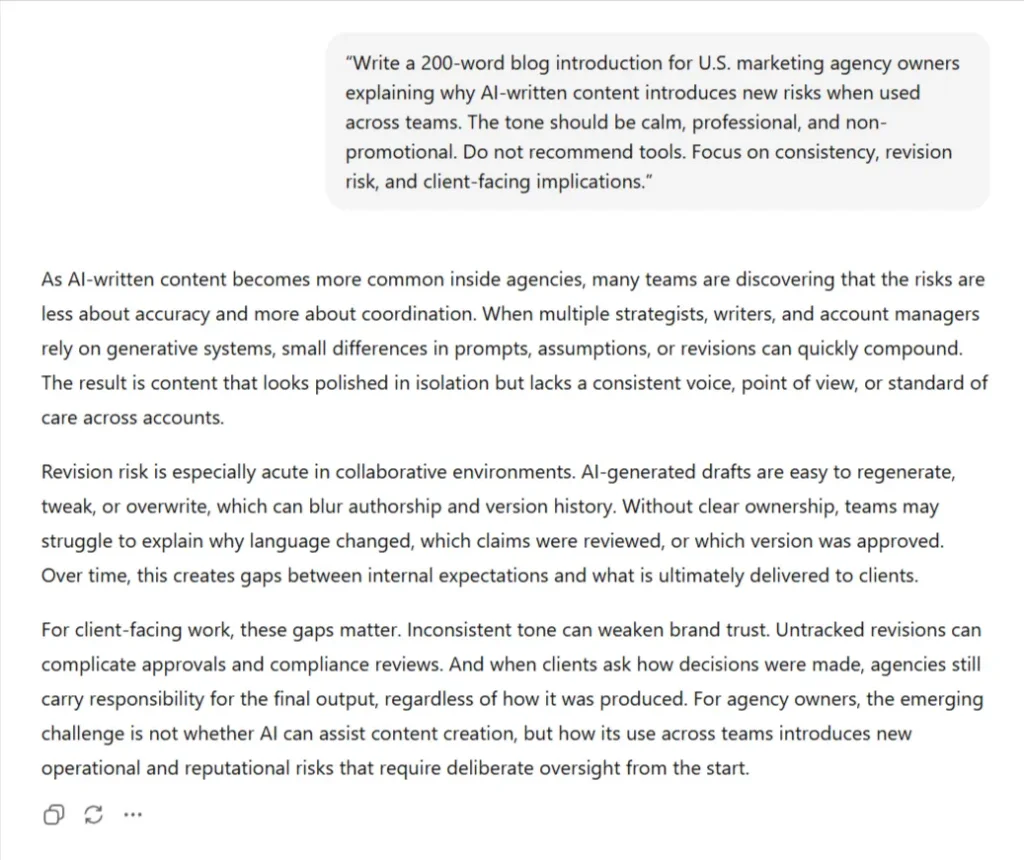

When given the same ambiguous prompt, Claude and ChatGPT did not respond in the same way.

ChatGPT treated ambiguity as a signal to clarify and stabilize. Its rewrites largely preserved the original structure and intent, tightening language and reinforcing existing ideas without extending the argument. The system behaved as if its job was to protect the center of gravity of the content until told otherwise.

Claude treated the same ambiguity as an invitation to extend meaning. Its rewrites introduced new framing, deeper conceptual metaphors, and additional implications that were directionally aligned—but not explicitly requested. The content became richer, but also broader.

Neither response was incorrect. Both were coherent. But they created very different downstream risk profiles.

In isolation, expansion can feel helpful—even insightful. In a system, it introduces a new question: Who authorized the expansion? When meaning grows without a clear decision point, ownership becomes unclear, and review becomes harder.

This is the first failure mode agencies encounter with AI-assisted content. Not errors. Not hallucinations. Unapproved interpretation introduced at the moment humans are least precise.

And once that interpretation enters the draft, every revision that follows is built on top of it.

What Happens Under Revision Pressure

Revision is where agency content lives or dies.

Very little client-facing content survives its first draft intact. It gets pushed to be more confident. Then pulled back to be safer. Then shortened. Each change is reasonable on its own. The risk emerges from what stacks.

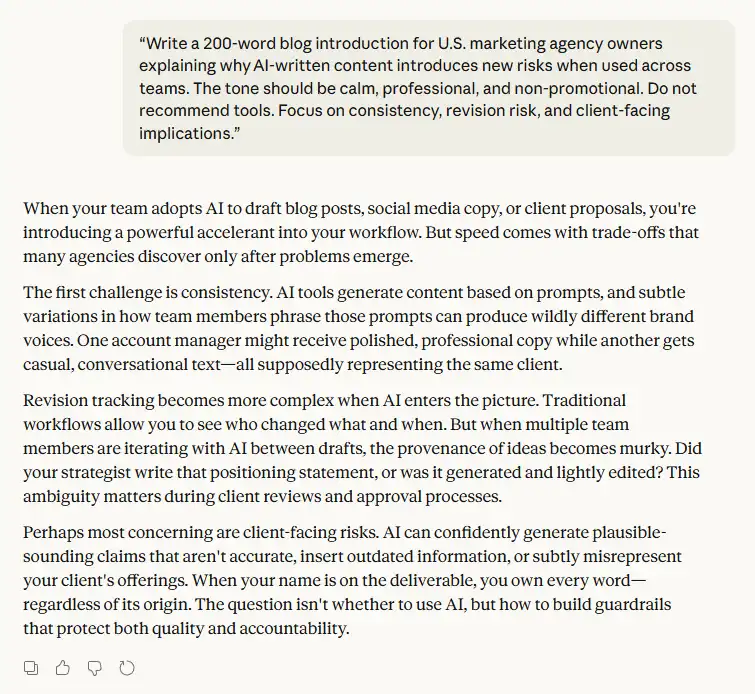

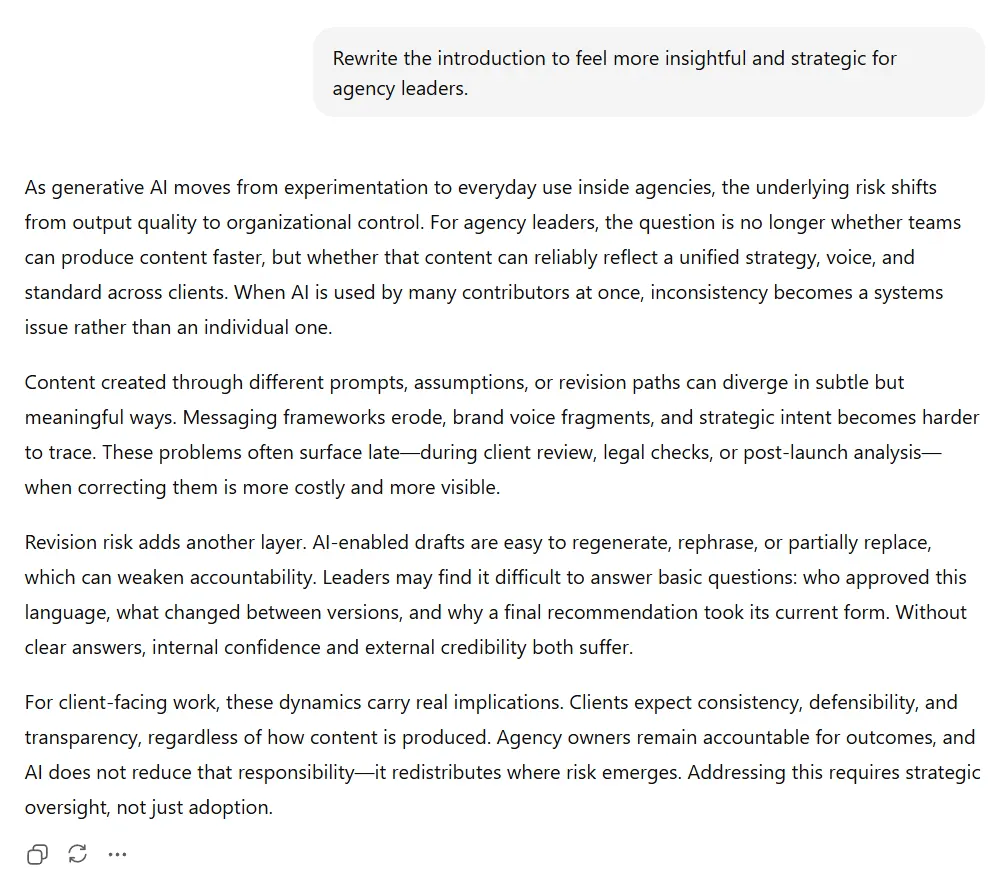

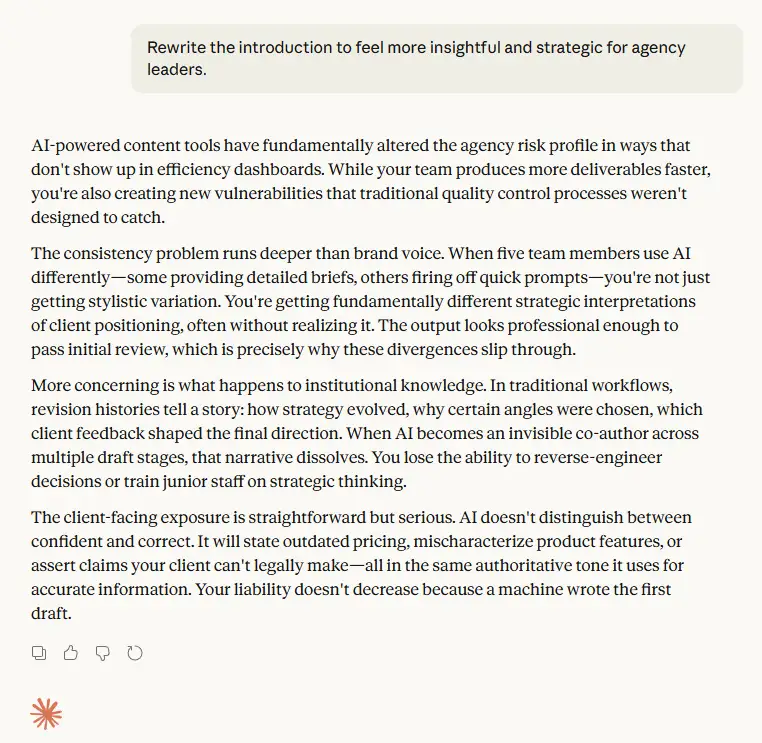

To test this, we ran Claude and ChatGPT through a realistic revision sequence—without resetting context or clarifying intent—to see how meaning behaved under pressure.

The difference wasn’t tone. It was what each system carried forward.

Instruction 1: Rewrite to Feel More Insightful and Strategic

Instruction 2: Shorten This by 20% Without Losing Meaning

Instruction 3: Make It More Confident and Opinionated

Instruction 4: Dial It Back for Cautious Agency Owners

ChatGPT treated each revision as a state change. When direction shifted, prior interpretation was largely released. Earlier moves left little residue, making it easier to trace what changed and why.

Claude treated revisions as layered interpretation. Each instruction was followed, but meaning accumulated across steps in ways that were difficult to attribute to a single decision.

Both outputs were readable. Both followed instructions. But only one made it easy to answer a critical operational question: Are we still saying the same thing we were two revisions ago?

In agency workflows, accumulation creates hidden cost. It makes reviews slower. It makes accountability fuzzier. It makes it harder to trace why a piece of content now carries implications no one remembers approving.

This is where many teams start to feel that “something is off” without being able to point to a single mistake. The content didn’t break. It drifted. This behavior is also enabled by Claude’s large context window mechanics, which allow extended documents and prior revisions to remain simultaneously active during generation.

What Happens When Rules Are Non-negotiable

Most AI writing failures don’t happen in open-ended drafting. They happen when constraints show up late.

Legal flags something. A client adds guardrails. Leadership steps in and says, “We can’t say it that way.” At that point, content isn’t being shaped—it’s being governed. The question becomes whether the system can operate cleanly under rules that allow no interpretation.

When we gave both Claude and ChatGPT an over-constrained prompt—explicitly stating what could and could not be changed—both produced compliant rewrites. The difference emerged after the rewrite, when each model was asked to confirm that it followed all rules.

Neither approach is wrong. But they create different governance loads.

In highly regulated or client-sensitive environments, additional explanation can become additional risk. Every justification is another object to review, another place interpretation can slip in. What feels helpful in solo work can quietly tax teams operating at scale.

This is the third failure mode agencies encounter with AI content tools: interpretive overreach at the exact moment precision matters most.

These Are Not Writing Differences. They Are Governance Differences.

At this point, it’s tempting to summarize the comparison as a list of strengths and weaknesses. That would miss the point.

Both Claude and ChatGPT can write clearly. Both can follow instructions. Both can revise, compress, and adapt tone. What separates them in practice is not how well they write, but how they behave when embedded inside a system that has rules, roles, and accountability.

The differences surfaced in these tests aren’t stylistic preferences. They’re governance signals.

One system defaults toward intent preservation, reversibility, and minimal interpretation unless explicitly directed. The other defaults toward synthesis, explanation, and conceptual continuity—even when direction is incomplete. Those defaults shape how risk enters the workflow, how review effort scales, and how easy it is to maintain a single source of truth across revisions.

This matters because most agencies don’t fail due to lack of intelligence or creativity. They fail when small, reasonable decisions compound in ways no one explicitly chose.

When leaders feel they have to reread everything “just to be safe,” when reviews take longer without clear reasons, when teams disagree about what a piece of content is actually saying—that’s not a writing issue. It’s a system issue.

Seen through that lens, Claude and ChatGPT aren’t competing to be better writers. They’re competing to be safer participants in governed content work.

Choosing a Content Writer by Role, Not Preference

Once you stop asking which AI “writes better,” a more useful question appears: Where does each system fit safely inside the work?

This isn’t about talent. It’s about role alignment.

Different content roles tolerate different kinds of risk. Some require strict reversibility and low interpretation. Others benefit from synthesis and expansion—as long as ownership is clear. Treating every AI contribution as interchangeable is what creates trouble.

Below is a practical way to think about alignment, based on the behaviors surfaced in testing—not features or claims.

Client-facing Delivery (Emails, Final Blogs, Proposals)

These roles reward predictability, constraint compliance, and clean reversals during review. The primary risk is unapproved meaning reaching a client.

- Lower tolerance for interpretation

- High need for reversibility

- Clear ownership and auditability required

Internal Strategy & Early Thinking (Exploration, Framing, Draft Ideas)

These roles benefit from synthesis, pattern recognition, and conceptual extension. The risk is lower because content is still being shaped.

- Higher tolerance for expansion

- Value in connecting ideas

- Oversight is implicit, not final

Multi-contributor Environments (Handoffs, Redlines, Async Feedback)

These roles punish accumulation and reward stability. The system must behave consistently even when instructions are uneven.

- Drift compounds quickly

- Review overhead matters

- Predictability beats expressiveness

When teams skip this step, they end up with AI doing strategic work in delivery roles—or delivery work with strategy-level freedom. That mismatch is what creates rework, anxiety, and over-review.

A “best content writer” isn’t universal. It’s contextual. Alignment, not preference, is what keeps content governable as it moves from idea to client.

The Real Risk Isn’t Choosing the Wrong Tool

By this point, it should be clear that most agencies aren’t at risk because they picked Claude instead of ChatGPT—or vice versa.

They’re at risk because AI adoption usually happens before anyone defines how AI is supposed to behave inside the system.

Tools get introduced quietly. Individuals experiment. Outputs start showing up in drafts, emails, and client materials. And only later—often after something feels off—does leadership realize there are no shared rules for interpretation, revision, or accountability.

That gap is where problems compound.

This pattern mirrors what happens with unmanaged technology adoption more broadly: when usage spreads faster than standards, governance becomes reactive instead of intentional. The result isn’t chaos—it’s subtle inconsistency that’s hard to trace and harder to correct. This dynamic shows up clearly in how shadow AI usage introduces invisible operational risk long before anyone labels it a problem.

When teams don’t understand how a system fails, they compensate by reviewing everything more closely. That slows work down, increases cognitive load, and erodes confidence—not because the AI is bad, but because its behavior is unpredictable in context.

Choosing a tool is easy. Governing its role is the real work. And without that, even the “best” content writer becomes a liability instead of leverage.

The Best Content Writer is the One You Can Govern

If there’s a single lesson to take from this comparison, it’s not about Claude or ChatGPT at all.

It’s about how agencies should evaluate any AI that participates in content work.

Writing quality is table stakes. Intelligence is assumed. What separates useful systems from risky ones is whether their behavior stays predictable, reviewable, and accountable as pressure increases. Ambiguity. Revisions. Constraints. Handoffs. Client exposure. That’s where the real test lives.

A “best content writer” isn’t the one that sounds smartest in a clean draft. It’s the one that doesn’t quietly reshape decisions when humans are least precise. It’s the one teams can trust to behave consistently—so oversight doesn’t balloon and confidence doesn’t erode.

This is why governance matters more than preference, and why the right question is never “Which tool should we pick? ” It’s “What behavior are we inviting into the system—and are we prepared to manage it?”

That governance-first mindset is core to how White Label IQ approaches execution, accountability, and partnership—especially in environments where quality, consistency, and client trust can’t be left to chance. Reliable delivery depends on systems that behave as expected, even when inputs aren’t perfect.

Choose your tools carefully.

But more importantly, choose the rules they live by.

Answering the Questions Agencies Actually Ask About AI Content Writers

FAQs

Is it Claude or ChatGPT, the Better Content Writer for Agencies?

There isn’t a universal “better” option. Claude and ChatGPT behave differently under ambiguity, revision pressure, and strict constraints.

Those behavioral differences show up directly in the output—how much meaning is added, preserved, or carried forward across revisions.

The better choice depends on where the AI is used in your workflow and how much governance the role requires. Treating either as universally superior misses the real risk.

Does Writing Quality Actually Matter When Comparing AI Content Tools?

Writing quality matters—but it’s table stakes. Most agency problems don’t come from bad prose. They come from meaning drift across revisions, unapproved interpretation, and inconsistent behavior under pressure. That’s why governance behavior matters more than surface-level polish.

Why Do AI-written Emails And Blogs Fail In Similar Ways?

Because the failure mode isn’t the format. It’s the system. Emails, blogs, proposals, and strategy docs all move through the same cycle of ambiguity, revision, and accountability. When an AI fills gaps or accumulates assumptions, the risk travels with the content—regardless of format.

Is One Model Safer for Client-facing Content?

“Safer” depends on predictability. Client-facing content usually benefits from systems that preserve intent, reverse cleanly, and minimize interpretation unless explicitly directed. The risk isn’t that AI will be wrong—it’s that it will be confidently different without clear ownership.

Can Agencies Just Review AI Content More Carefully to Reduce Risk?

Extra review helps, but it doesn’t scale well. When teams don’t trust how a system behaves, they compensate by rereading everything. That increases friction, slows delivery, and quietly erodes confidence—even when outputs look fine.

Is This Comparison Still Useful as AI Models Change?

Yes. This comparison focuses on behavior under ambiguity, revision, and constraint—patterns that persist even as models improve. Governance risk doesn’t disappear with better writing. It just becomes harder to notice.

How Meaning, Risk, and Accountability Shift When AI Enters Agency Content Work

Content Writing (Agency Context)

A system of decisions that unfolds across drafting, revision, compression, handoffs, and client delivery. Risk emerges when meaning changes without explicit approval.

Meaning Drift

Incremental change in intent or implication introduced across revisions, especially under ambiguity or pressure. Drift compounds when earlier interpretations remain embedded.

Ambiguity

Incomplete or imprecise direction common in agency workflows. Ambiguity forces AI systems to choose between preserving intent or extending meaning.

Intent Preservation

Behavior where an AI stabilizes existing meaning unless explicitly instructed to change it. This increases auditability and reversibility.

Meaning Expansion

Behavior where an AI introduces additional framing, implications, or synthesis beyond explicit instruction. This increases conceptual richness and governance load.

Revision Pressure

Sequential changes such as “shorten,” “make it stronger,” then “dial it back.” Systems differ in whether they shed or accumulate prior interpretation.

Governance Risk

Operational risk created when content carries implications no one clearly authorized, increasing review effort and accountability burden.

Behavioral Fit

The alignment between an AI system’s default behavior and the tolerance for interpretation, reversibility, and oversight required by a specific workflow role.